- artist:Jaraba Jakite, Yamadu Dunbia

- featured artist:Jaraba Jakite, Yamadu Dunbia

- release year:2006

- style(s):Afro, Percussion

- country:Mali

- formats:Book

- record posted by:bibiafrica music edition

- label:bibiafrica music edition

- publisher:bibiafrica music edition

- buy this record

Links

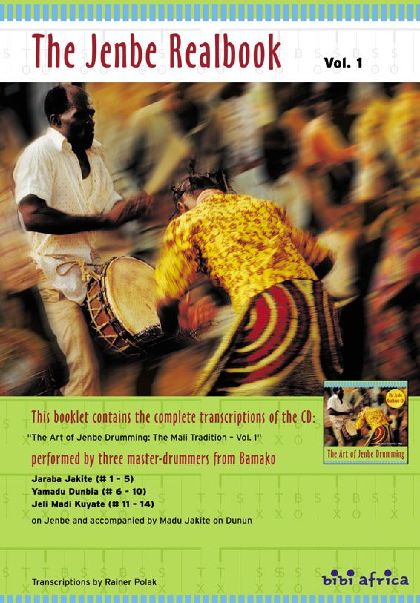

This book contains the complete transcriptions of the CD:

»The Art of Jenbe Drumming: The Mali Tradition Vol. 1«

The CD was recorded 1995 in Bamako by Rainer Polak, first released with Bandaloop Records in 1996 and re-released with bibiafrica records in 2006 (www.bibiafrica-records.de)

The transcription follows the order of the CD tracks

1 Intro + Fula 04:25, 2 Madan 06:25, 3 Maraka 04:44, 4 Sogoninkun 04.43, 5 Sabaro 04:55, 6 Woloso 04:20, 7 Kòmò 06:50, 8 Kòfili 05:37, 9 Kirin 05:12, 10 Burun 03:48, 11 Maa Nyuman 01:44, 12 Jina I 04:18, 13 Jina I 02:52, 14 Jina III 02:41

The music was performed by

Jenbe: Jaraba Jakite (Tracks # 1 – 5), Yamadu Dunbia (Tracks # 6 – 10), Jeli Madi Kuyate (Tracks # 11 – 14), Dunun: Madu Jakite (all tracks)

The recordings

In the recordings, three masters of traditional jenbe dance drumming present the clear beauty and explosive power of their music. Of course the music of a jenbe dance celebration cannot be adequately documented because it represents part of a dynamic event which can only be fully grasped by witnessing all its interlocking elements. The sound recording of a celebration would lack the movement of the dancers and the whole atmosphere of colors, smells, and enthusiasm. The recordings presented in this CD, moreover, were made not in the context of a celebration at all, but in a school yard in the Badialan quarter of Bamako. The drummers performed for the microphone, without rehearsals, without arrangements, and without an underlying notion on how to convey celebration music without a celebration. It was the first time to do a studio recording for all of them. They spontaneously created a kind of »art music« in a space without references, an abstract translation of music traditionally played for celebrations. The original live tracks were neither cut, nor overdubbed.

The ensemble

The CD presents masters of the jenbe in duet performances with an accompanying bass drummer – one jenbe, one dunun, no bells. Playing in this smallest version of a jenbe drum ensemble was typical for the celebration music style of Bamako in the 60s, 70s and 80s. Today, trio, quartett, and even larger ensembles are the rule, and many stylistic influences from ballet music, the playing styles of Conakry and Abidjan, and of the international jenbe scene based in the rich West, have come to change the Bamako style. Thus the recordings featured here represent sort of a classical aesthetic ideal of Malian jenbe music as crystallized in its capital Bamako after independence.

Only mature musicians can master duet playing and know how to create its typical fascinating musical density, balancing the tension between flow and transition, between communal groove and individual expressivity, between tradition and improvisation, between form and trance. The »challenge of the void« that duet playing presents to many holds no threat for the drummers of Baladian, because their playing is based on decades of experience as performers in this sort of ensemble. Fabulously sure of their instruments, guided by close communication even in the boldest passages, the void represents space they enjoy to fill with sound.

The reduced line-up also has the advantage of very clear and transparent sonic reproduction. Thus the listener can not only perceive the fundamental musical structures, but also experience the high art of drumming, the »talking of the drum«, in its finest rhythmical nuances and timbral shades.

The transcriptions

As has become usual since the 1960s in studies of West African percussion music, the notes are set in relation to a graphic raster that represents a linear metric system of elementary pulses (smallest time units except of rolls/flams) and beats (comprising either 3 or 4 pulses to larger units). Thus all rhythms transcribed refer to either a quaternary metric system of 16 pulse cycles (4 beats x 4 pulses) or to ternary 12 pulse cycles (4 beats x 3 pulses).

The following sound symbols are used in the transcriptions:

S jenbe slap

S closed or muffled jenbe slap

T jenbe tone

B jenbe bass

X closed or muted dunun stroke

O open dunun stroke

Without doubt, the transcription published here do not make an exception from the rule that a musical transcription can always be only an imprecise and incomplete approach to represent a sonic reality. Working with the book makes sense only if the reading of the music comes along with hearing the CD. Hearing the CD, plus of course hearing other jenbe music, continuous practicing basic skills like sounds etc, and studying with a good teacher, are much more important than working with the book, and are preconditions to being able to successfully work with the book.

Let me hint at some of the most important aspects of the music that are not adequately represented in the notation. While the basic sounds of the jenbe (bass, tone, slap) are pretty clearly discernable most of the time, they are not transcribed in their further differentiations or fluid transitions. For instance, sometimes bass tones are played so softly that you can also interpret them as “ghost notes” or “tips”. Slaps as played by Dunbia and particularly by Kuyate are often almost, yet not completely closed, making it difficult to make a clear-cut distinction between open and closed slaps. While these “dirty” sound characteristics are typical for the duet playing style of Bamako, and important to the musical result, they are very hard to transcribe. This is the case even more so with the phrasing of the rhythmic patterns. Malian jenbe playing, and duet performance in particular, literally lives by metric feelings that make the rhythm swing. If you measure in milliseconds the densificating ornaments performed by the three jenbe soloists, you will find that most of them do neither go conform with any linear derivation of the basic pulsation (double-time, sextoles, or the like), nor correspond to what is termed a “flam”. They are usually “broader” than a flam, and are unevenly structured: they represent patterned microrhythmic structures – the setting of which in the framework of a metric raster of elementary pulses is unjust and arbitrary. Even the basic pulsation itself frequently is not evenly spaced, as supposed by a linear metric understanding and notational system, but compressed and stretched alternately, in ways that produce rhythmic swing. This feeling can be applied to such an extent that the distinction between binary (or quaternary) and ternary rhythms begin to dissolve. For instance, while the dunun pattern of rhythm Burun is ternary, Yamadu Dunbia consistently phrases many of his jenbe patterns in a way that is very much in between a ternary (XxxXxx) and quaternary (X.xxX.xx) feeling. This is not due to ideosyncratic personal style or weird improvisations, it rather is inherent in the composition of the rhythm and its basic patterns. When measured, one even finds that the actual phrasing sometimes is closer to a quaternary pulsation (four pulses per beat) than to the dunun’s ternary feeling. Or listen to Jina 1, where many an allegedly quaternary pattern turns out to feel like being ternary. Structures of micro-timing is about the hardest thing to transcribe I can imagine, yet so essential to the music in question that this difficulty really means deficiency. At the moment I have the privilege to do more research on the timing of jenbe rhythms with the generous help a the German Research Council (DFG). I hope that this research will allow me also to think over the assumptions and delimitations of raster notation, and accordingly try to develop its capability to consider micro-rhythmic phenomina.

Bayreuth, spring 2006 Rainer Polak

The author

Dr. Rainer Polak studied social anthropology, African liguistics, Bambara language, and History of Africa from 1989 to 1996 at Bayreuth University (Germany), and jenbe music performance from 1991 until today in Bamako (Mali). All of his studies and work in Bamako were accomplished with the help of the musically outstanding, yet rather locally and traditionally minded drummers whose playing is presented in this book and the corresponding CD. Polak has worked as a professional jenbe player in Bamako for one year in 1997/98, performing at well over a hundred traditional weddings, spirit possession dances and other celebrations on the basis of being hired by the late Jaraba Jakite, most of the times, and occasionally by the late Yamadu Dunbia, by Jeli Madi Kuyate, and by Drissa Kone. The ethnomusicological dissertation and book he wrote on that experience won the academic prize of the German African Studies Association in 2003/04. Polak ranks as an outstanding jenbe soloist in Germany. As a teacher he has specialized in giving focussed classes on micro-timing, and master-classes in jenbe solo performance.