- country:Italy

- style(s):Ethnic, Jazz

- label:ECM

- artist posted by:Bremme & Hohensee GbR

Links

Gianluigi Trovesi / Gianni Coscia

In cerca di cibo

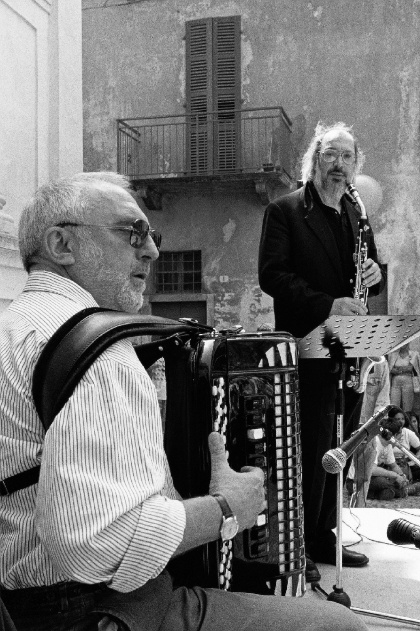

Gianluigi Trovesi: clarinets; Gianni Coscia: accordion

Umberto Eco, in his liner notes written especially for this ECM album, writes warmly of the way in which the accordion of Gianni Coscia gave him, in Italy of the 1950s, his initiation into the world of jazz, and continues, “I followed Coscia’s maturing talent up to his meeting with Trovesi and I find that there is now something particular about their experimentation, which is no longer the jazz of the early days but it’s not an attempt to get Armstrong into Carnegie Hall either.”

Here, Eco argues, “we are in the presence of a new transversality where distinctions of genre are van-ishing, while a certain attention is being paid (and this is something new) to Italian folk music...In [their] play of references to different texts and traditions, they occasionally arouse systems of expecta-tions within the listener that they suddenly frustrate, by changing the rules of the game. Which is one of the characteristics of experiments, a characteristic assumed in this case without foregoing some-thing that experimental music often foregoes, that is to say pleasure.” Indeed: the pieces on “In cerca di cibo” work on more than one level, but the most immediate quality the music conveys is the affec-tion that the players share in it.

Gianluigi Trovesi and Gianni Coscia have travelled, individually, through many musical idioms, but “In cerca di cibo” is firstly a celebration of roots, of “radici”. Trovesi and Coscia are old friends, from towns on either side of Milan – Trovesi from Nembro and Coscia from Alessandria (also Eco’s home-town) – and the music they play in duo re-examines the sounds that were in the air back then. It is music filtered through memory and nostalgia as well as through the worldly wisdom acquired along the way. Sometimes it is deeply sentimental, sometimes a cheerful irony comes into play. In this soundscape the Modern Jazz Quartet’s “Django” is brought back to its European folk roots. Pieces by Milanese composer Fiorenzo Carpi (1918-1997) – including fragments of his score for Luigi Comencini’s “Le Avventure di Pinocchio” (with Gina Lollobrigida in a leading role) – rub shoulders with the slinky tango “El Choclo” which Astor Piazzolla liked to play but which, in the present treat-ment, finds an almost Klezmeresque flourish in Trovesi’s yearning clarinet, as well as a piece by En-nio Morricone’s protege Luis Bacalov, the Argentinian-born soundtrack writer best known for his film-score contributions to the “Spaghetti Western” genre (including a quite different “Django”). The themes of Carpi, who was also associated with the political theatre of Dario Fo and Giorgio Strehler (long-reigning director at the Piccolo Teatro Milano) have a special resonance for the clarinettist and accordionist. Beneath its often simple surfaces, then, this music is densely-packed with cultural cross-references.

Long regarded as a musician’s musician, Gianluigi Trovesi has been finding a wider audience inside and beyond the borders of Italy in recent years. Arguably the most gifted soloist in that fractious big band full of soloists, the Italian Instabile Orchestra (see “Skies Of Europe” ECM 1543), Trovesi has also been heard as the leader of his own ensembles, particularly an inspired octet that has been a regu-lar presence on the festival circuit.

After a thorough classical grounding on the clarinet, Gianluigi Trovesi earned his living in the 1960s and early 70s playing almost every conceivable kind of music from dance bands to orchestral music to jazz ancient and modern. His soloistic brilliance was first showcased in the Giorgio Gaslini Quintet. Amongst his contemporaries, however, Trovesi was unusual in his conviction that a European jazzman had to make sense of his own geographical location, and in his trio, formed 1977, he explored the bor-derlines between Italian folk music and experimental jazz (in some ways his work in Italy paralleled that of John Surman in Britain).

From the 1980s onwards, he worked with a wide variety of leading international musicians, including Anthony Braxton, Lester Bowie, Misha Mengelberg, Kenny Wheeler, Steve Lacy, Barre Phillips, Evan Parker, Horace Tapscott, Louis Sclavis, Keith Tippett, Tony Oxley, Michel Portal and many others. He also formed several enduring alliances with musicians in Italy including Giancarlo Schiaf-fini, Pino Minafra, the Tiziano Tononi/ Daniele Cavallanti group Nexus, also working with Enrico Rava’s Electric Five.

Gianni Coscia, after completing classical high school studies, was a lawyer for many years, work that relegated music to the back-burner. Even in this period however he played with visiting American musicians including Joe Venuti, Bud Freeman and Sir Charles Thompson. In 1985 he released a widely acclaimed album “L’altra fisharmonica” which featured his accordion in combination with a string quartet and explored variations on Italian popular themes. “La Briscola”, a 1989 recording, sig-nalled a reunion with Trovesi, who has partnered the accordionist in many projects since then. Coscia has appeared with the Giorgio Gaslini Big Band and worked with orchestras playing music of Kurt Weill and Astor Piazzolla, and toured the world as accompanist to singer Milva, also working with Gioconda Cilio, Mariapia De Vito and Lucia Minetti. He has also collaborated with Enrico Rava, Pino Minfra, Paolo Damiani and other Italian improvisers.

In 1995, Trovesi and Coscia released their first duo album, “Radici”, on the small Italian Egea label. Confounding expectations for local “jazz”, it proved an immensely popular recording and has been reprinted six times. The communicative power of the duo’s music has also been very much in evi-dence at their concerts where they continue to bring down the house, as the saying goes, with their fluid, witty, trenchant music.

Umberto Eco points out, “The execution can be appreciated at a ‘high’ level, upon which the listener grasps the intertextual references, and at a ‘low level’, as music tout court, without being disturbed by artful or erudite references (...) This then is one way to add a popular dimension to cultivated music and a cultivated dimension to popular music. So there’s no need to wonder about in which temple we should place the music of Coscia and Trovesi. On a street corner, or in a concert hall, they would feel at home just the same.”