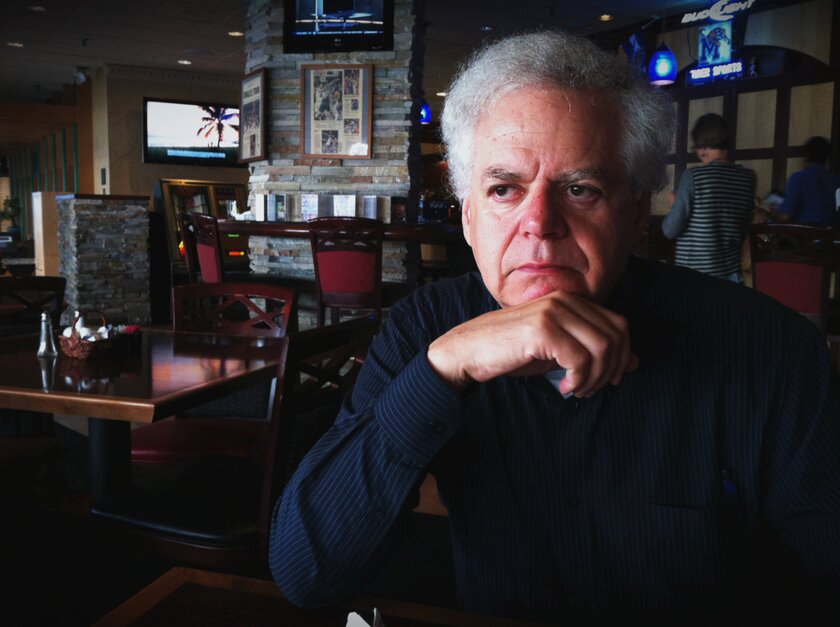

Written by Banning Eyre

Jeremy Marre’s 14-part Beats of the Heart film series more-or-less wrote the book on how music documentaries should be made. In a real sense, everyone since has worked in his shadow. Marre, who died at 76 in March of this year, went on to a long career in film, but there’s little doubt that he will mostly be remembered for the extraordinary Beats of the Heart series, which literally revealed worlds of music, before the term “world music” came into vogue. The films were made in the 1970s and early 80s in the Caribbean, Africa, South America, India, Asia, Europe and the U.S.—pretty much all over the world. What unites them is their focus on the complex and often punishing social circumstances that shaped the music and the lives of the musicians. It is as if situations of poverty, oppression, marginalization literally called forth the music as a necessary and non-negotiable expression of despair, desire, hope and hopelessness, an expression that nothing else could match.

As a young filmmaker in London, Marre first delved into music documentary with a film on British reggae. That led to his 1977 visit to Jamaica, where he revealed the music’s sources at a time when Jimmy Cliff, The Heptones, The Abyssinians, Bob Marley and Toots and the Maytals were just approaching international renown. But it is clear in Marre’s debut Beats of the Heart exploration that this era of reggae music was not about stars and international careers, but messages, messages that needed above all to move local listeners. Reggae was then, as one artist notes, “the rhythm of the ghetto and lyrics of the street.”

This film, Roots Rock Reggae, is one of four Beats of the Heart titles featured at WOMEX this year, the four earliest in the series. In Rhythm of Resistance , Marre ventures into apartheid South Africa in 1979, years before Paul Simon’s Graceland, and once again finds the creation of music as a lifeline for people facing unimaginable oppression. Censorship was an institution so there was no chance of recording protest music. Protest had to be implicit, as in Zulu migrant workers doing their high-stepping, skull-crushing dances on their days off, or young Sipho Mchunu performing Zulu folk songs with a boyish white musician identified only as Johnathan—Johnny Clegg and Juluka had yet to be formed. This is particularly a potent time capsule, given all that has gone on in South Africa since. The film takes us to hidden places, like a town hall packed with township fans of rowdy, raucous mbaqanga music. The film culminates in an all-night choral singing contest in a hostel, with a white man recently released from a 10-year prison sentence as the judge, since no one within the workers’ community could be trusted to be objective.

In Salsa, also 1979, Marre portrays the lines of culture and ambition that connect the poorest neighborhoods of Puerto Rico with New York’s South Bronx. Music and dance grace the streets in a gritty urban landscape. Nostalgia, spirituality and the rhythmic force of the musicians’ African legacies propel a sound that has since proven timeless and unstoppable. An acoustic guitar performance by a very young Ruben Blades is priceless. But here again, Marre is less interested in the mechanics of the music or individual performances than in the people, and the underclass lives that compel them to create and to consume music that could only exist in their world.

The fourth film, Konkombe , takes us to Nigeria at a time when Juju music was king, and Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat sound was a relative newcomer. Today, when a new and far more commercial strain of Nigerian pop has all but taken over the African continent, and much of the world, it is worthwhile and fascinating to revisit a time when it was all about the local scene.

In Marre’s films, the voices we hear are always participants in the story. There are no omniscient narrators and subtitles appear only when absolutely needed. His goal is always to bring the viewer in close, never to observe from afar. This is why, no matter how much the world changes and music evolves, these films will always captivate viewers. They capture a unique era, the dawn of cultural globalization, a time where music was still a local concern, and a driving force at the heart of struggling societies.

Banning Eyre is Senior Producer at Afropop Worldwide and

afropop.org.

As part of WOMEX Film's continued community engagement, a special retrospective of Jeremy Marre’s award-winning series Beats of the Heart was available to stream online from 24 September until 8 October 2020 for all WOMEX 20 Digital Participants.

article posted by:Sana Rizvi, Piranha Arts