Interviewed & Written by Sana Rizvi

Dear WOMEX Community,

As a lot of us are spending more and more time at home, we invite you to take a look at the April selection of films in the WOMEX Films on Demand section. Extraordinary times call for extraordinary films and we have just those in store for you - Jawad Sharif's Indus Blues and Paul Duane's While You Live, Shine .

Both these films revolve around the preservation of music, musicians and the broader community working with traditional art forms, allowing for deep reflection, compassion and connection in times of extreme uncertainty and anxiety.

You can watch these films on demand here for the next month at any time convenient to you once you log into your virtualWOMEX account. If you have any questions, please feel free to email us at film@piranha-arts.com.

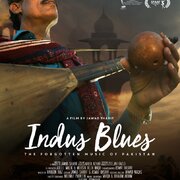

We had a chance to speak with director Jawad Sharif about his film Indus Blues - a work of rare authenticity that despite its simple structure emerges as a complex, multilayered and moving portrait of the Pakistani folk music scene, its veteran musicians and craftsmen who are barely surviving in an indifferent society.

You can also read a previous interview with musicologist Christopher King who is the main protagonist of the film While You Live, Shine here.

Where did the idea for the project come from?

Jawad Sharif : The core idea of the film comes from a very personal space. A couple of traditional musicians are friends of mine. Over the years of knowing them and having conversations, I realised how difficult it was for them to be a musician in Pakistan and the resistance they face not only in society but within their own families. I could personally relate to this resistance as well since being a filmmaker myself, I have faced the same from my family. They also wish I would get a "real & respectable" job. I also have a deep love for traditional, folk and classical music from Pakistan, and this attachment pushed me to make Indus Blues.

How long did the research process take and how did you shortlist the instruments and the craftsmen you wanted to document and showcase through the film? Talk us through how the narrative of the film evolved while making the film?

Jawad Sharif : It took us at least 2 years in research before we even began travelling across the country to meet with the musicians. We had shortlisted 24 endangered instruments that we found through our research, but then it turned out that there were no players or makers left of some of the instruments and some others we couldn't film so, in the end, we focussed on 9 of the instruments shown in the film.

The narrative evolved over time with each meeting with the musicians and craftsmen. And as we started filming and going back to shoot on location, we also realised how much resistance the musicians faced in their villages and homes. The final film is not at all the film that I had initially conceived, and I suppose that's what documentaries are in a sense- an evolution of the storyline which enables one to make the story more dimensional than flat.

Why did you feel that it was necessary to highlight not only the musicians but also the makers of these endangered instruments?

Jawad Sharif : Normally, what happens is that we generally get to see and hear the musicians. But we rarely get to meet or hear from those who are behind the scenes- the craftsmen of the instruments. My thought was that the craftsmen are musicians themselves and equally knowledgable about the art. They know all the notes or like we call "sur" and if they didn't, then the instruments wouldn't be in tune. It was essential for me to portray this part of the traditional music world in Pakistan as well. But it turned out to be much more challenging to locate the craftsmen that we have shown in the film, and we travelled long distances to find them. It was completely worth it as the film would have felt incomplete without them.

Was there a reason why you choose to base your film in a region around the Indus River?

Jawad Sharif : The Indus Valley civilisation (3300-1300 BCE) situated along the Indus river has been a civilisation of incredible importance and cities such Harappa, Ganeriwala, and Mohenjo-daro have been great centres of innovation, infrastructure and culture. This was a perfect starting point for our research plus shoot to discover rich musical traditions of Pakistan. The river also happens to run the entire length of the country from north to south, so we travelled over 2000 miles covering many varied regions that lay along the river.

What were the challenges faced by you and the team in completing the film?

Jawad Sharif : Oh there were many hurdles to cross - from resistance on location while shooting, animosity while we were out on the field meeting with musicians and even trying to get the artists to trust us and to speak to us about their hardships

Post-production, we were trying to figure out how to edit all these stories through one narrative thread. And then, of course, securing funding and distribution plus getting censor certificate for the film so that it could show across Pakistan were not easy at all.

Did you find it easier to talk about a wider range of socio-political and religious issues faced by Pakistan through the medium of music?

Jawad Sharif : Freedom of expression is almost non-existent in Pakistan. It is complicated to talk about sensitive topics such as religion or state openly without repercussions.

So yes music, was definitely a kind of shelter and tool through which we could have a covert dialogue on sensitive topics with the artists and have them open up more. Having said that, parts of the film which touch upon religion when it comes to music have been censored in Pakistan, where an edited version of the film is screened.

Why do you think there is a disowning of the culture on such a large scale in traditional music?

Jawad Sharif : I think there are several factors for this. One is due to globalisation and the impact of the western more commercial music industry on the local one. But the major reason, in my opinion, is that as a generation, we suffer from a huge identity crisis in which we don't consider traditional and folk music as part of our culture. An entire generation has been brainwashed to think that these art forms belong to India or Hinduism, which we have turbulent relationships with. So we have been forced to identify ourselves more with a religion which doesn't consider this as our culture even though for me, they are two very different things- religion and culture.

Has the film been received by audiences in Pakistan? Also, how does one create ownership of the culture within the country?

Jawad Sharif : The trailer went viral within a day and got over a million views as soon as it was released in Pakistan along with mainstream news channels covering this independent film. Even though the trailer and the film were censored in the country, it was able to spark debates around the story. It is great that an urgent topic that was so hidden from the mainstream even among the aware, educated urban elites of Pakistan is brought to the forefront. We have had several screenings across Pakistan to full houses. The film has created awareness and impact among the public, even leading to one school offering a job to a musician showcased in the film to give music classes to students.

Indus Blues is just the first step to create awareness, and I hope the state institutions take the necessary steps to preserve our traditions and culture be it in music or other traditional art forms.

Thank you so much Jawad for your time. Before we wrap up here tell us what are you listening to nowadays in terms of music? What project(s) are you working on currently?

Jawad Sharif : It was beautiful attending WOMEX 19 since I had the chance to learn about some incredible musicians from across the globe. I am currently listening to Kayhan Kalhor, who I first heard at WOMEX. I am currently working on a film about a friend related to gender politics in Pakistan. Can't say too much about it just yet!

article posted by:Sana Rizvi, Piranha Arts