Pedro Coquenão aka Batida was born in Huambo, Angola, and raised in the suburbs of Lisbon, Portugal. He creates and interacts with music, dance, visual, plastic and radio arts under the name Batida, meaning 'beat' in Portuguese and relating to the dance music culture of Luanda.

- 23-27 OCT 2024

- Manchester, UK

Lisbon exposes you to all this diversity

Interview with Pedro Coquenão aka Batida

20 April 2022 by Lucia Udvardyova

Pedro Coquenão aka Batida

Lisbon seems like a significant symbol within the context of your work; tell us a bit about your connection with this city.

I was born in what was then called New Lisbon; now Huambo and my family were fortunate enough to be moved into Lisbon because of the war in Angola. This city has developed a lot along with the people coming from former colonies, but the history goes way back. It was a pivotal city involved in the slave trade. Personally, it’s a city I connect with because it has a history that goes back to my former country (Angola). Culturally and socially, Lisbon is a city like any other: with lots of challenges, but at the same time it has a huge potential to confront and resolve most of them due to its history. It’s also part of Europe, but it mostly faces the ocean and other continents such as the Americas and Africa, which I relate to. I can see the reflection of my identity here as I can look back on history, project myself and be part of where I'd like to see myself in the future.

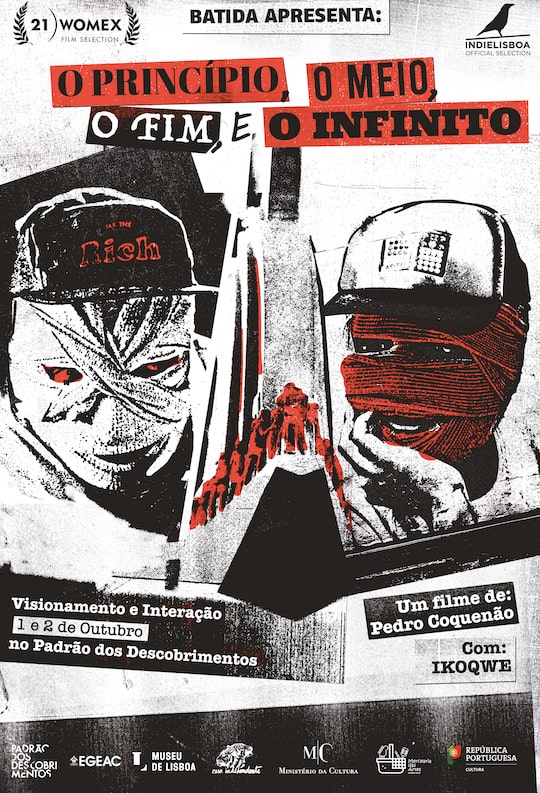

Your film O Princípio, O Meio, O Fim e o Infinito seems like a metaphor of all these thoughts: the city, colonialism, and history. But it’s done in an abstract, poetic way. All these social and historical issues are woven into this playful narrative, framed by the city of Lisbon.

I tried to make it enjoyable, but the thing that I try not to play with are the hard facts, the basics: inequality still exists, prejudice still exists and they have a context. My film was screened inside the biggest monument that talks about the period when Portuguese people departed from Lisbon to start what was then known as the “discoveries” and the consequent slave trade market where Portugal was one of the biggest countries “transporting” humans as slaves. If I have to comment, I prefer to do it musically or artistically, so we can wonder about it. We have to be able to dream. I like to make people laugh; I like to provoke and entertain and try to bring people together. My family is Portuguese and Angolan, and I would love at least for these two families to engage in a better dialogue other than just economics.

My aim is to make people think about it because it’s an issue that is still quite present; it’s very structural and systemic. In Lisbon, this is quite evident and easy to trace back. People don’t like to hear it because no country likes to be known as racist. Sure all countries are racist, but Portugal has a way bigger responsibility - bigger than its strategic position these days - in this respect because of its history.

_____________________________________________________________________

Music is very important for the rhythm of the film and for yourself, as your background is in the music scene. You've worked in dance, music, visual, plastic and radio arts under the name Batida. Contemporary Lisbon labels, like PRÍNCIPE, that release music by Lisbon's African diaspora, are paid homage to in the film. Could you talk about the musical connections of the feature?

This happens naturally because I like to bring everyone together, even if it's just in my head. I’ve worked in radio since I was a teenager and as a kid I always used to involve all my cousins and neighbours in whatever I was doing. It’s in my nature to try to bring people together, especially in this kind of narrative, which is not exclusively mine. There are lots of things in common: a sense of being here, but not really being part of this country because there is always something off with you. Artistically speaking, to be living in Lisbon exposes you to all this diversity. This city has the potential for being unique in its synthesis between all these strong connections to Brazil, Angola, Cape Verde, and mostly observing the rest of the Western world . Your body and movement are definitely more specific here because of these relations. Movement is my favourite way of expression, actually.

What is the significance of the masks - balaclavas that are worn by the characters in your film?

They are medical textiles. The characters in the movie are two friends who believe they come from somewhere else because they lost their memory. They live in the present and try to understand what’s going on around them. Because I know a bit about their personal history - at least one of them had a huge burnout and couldn’t face reality as presented. The mask acts as a defence and protection against the violence that surrounds them. It’s a very literal metaphor about being burnt and not being able to allow the skin to come into contact with the normal atmosphere. It’s a post-burn atmosphere. When you are growing up as a kid, you hope all these things will change during your lifetime, but then you realise your life is really short and eventually you can only contribute or witness slight improvements, and those improvements also end up where they were ten years ago. Two steps forward always force you to take one step back but the outcome is positive. At least we have to believe so.

What does the term “neon-colonialism”, which features in the film as well as your other works, mean?

Artistically it can be many things: me being playful. Anything in neon sounds and looks great. It’s trying to put the word colonialism on a strange medium with handwriting that I learned in primary school that still had old ways close to the former dictatorship. There’s this talk of the new Lisbon being modern and sexy and neon is sexy. I don’t like the term and I believe that the concept overlooks most of its past. I am focused on the future but it scares me to move with no context and acknowledgment, which may facilitate inhuman narratives to return. Sure, there are “new” things happening and this potential but at the same time, we are still dealing with postcolonialism, neocolonialism or neon- colonialism (being colonialist in a shiny, sexy way).

_____________________________________________________________________

You also have a new film called The Almost Perfect DJ.

I wanted to present something new at Eurosonic, and I was at the end of my wits in terms of my mental health. I was really drained. I flew straight from New York to perform at Eurosonic, and it was horrible. I cancelled everything after that performance. Once I was able to rewrite and perform it, I decided to create a performance that would somehow put a light on the DJ’s position as a comparison with the modern representation of being human. I started being a DJ just because I liked music and I liked to be in the darkest spot in a room, making people dance. And then this position evolved from someone that was mostly discreet and musical into someone that was more of a performer and a central figure, and that intrigued me. Usually a DJ is a (white) man, elevated from the rest of the dance floor…all the potential of the dance floor was being taken away by the figure of the DJ who claimed all the attention to themselves. It also reflects our society as we are the ones who validate this moment. The film is about that performance and it’s about growing up in Lisbon, so it’s also personal too: it’s about my journey from a bedroom DJ to playing at big festivals. It’s about (bad) representation and democracy. #powertothedancefloor

You participated at WOMEX in Porto in October 2021. What were your impressions?

I usually don’t feel comfortable in places where I have to explain or sell myself. As an artist, I try to avoid those kinds of environments. I went to WOMEX because my previous experience with it in Santiago had been great and life- changing. It started with the programming and production being spot on and caring. I could see that the people were really passionate about what they were doing and focused on making me feel good about how I would present myself. I had been cynical about it, thinking that the audience would be very professional, checking technicalities and budgets etc. By the end of the show, the response that I felt from the audience was not coming from the “technical” crowd, but from the people genuinely passionate about music. I felt hopeful with the “industry”. When I heard it would be in Porto, I wanted to be involved. There were people at my screening from Portugal that I had never met before, along with new and old friends. To make it work for you, as an artist, it’s important to have your team involved, in my case it was key to have my booker Clementine with me to make the best out of it. No one gets anywhere alone. I want to go back and I think that is the best testament to my experience.

_____________________________________________________________________